RainbowPUSH Coalition

The RainbowPUSH Coalition was founded by Jesse Jackson, Sr. when he merged Operation PUSH (People United to Serve Humanity) and the National Rainbow Coalition.

It is affiliated with the United for Peace and Justice.[1]

Re-inventing the Rainbow Coalition

In a statement released in November 2016, the Democratic Socialists of America National Political Committee referred to the Rainbow Coalition as a model for today’s anti-Trump resistance: “Under Reagan, similar acts of resistance eventually created a powerful rainbow coalition that advanced a multiracial politics of economic and racial justice. If we fully commit ourselves to these struggles over the next four years there is no reason why a new, even more powerful multiracial coalition for social and economic justice cannot emerge.”[2]

Communist direction

At the time of Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election, the political situation was moving rapidly to the right. The Democratic Party was in retreat, trying to find the way to recover from the blows. In 1984, the left wing of the Democratic Party and its satellite organizations attempted to win the primaries through the Rainbow Coalition, headed by known Civil Rights Movement figure, Jesse Jackson. The goals of the campaign were to oppose Reaganomics and gain support from Blacks, working-class people, immigrants, women, and the LGBT community.

A significant portion of the left found it necessary to back Jackson’s campaign, or risk missing out on an important political opportunity. Organizations like the US League of Revolutionary Struggle (M-L), Communist Party USA (CPUSA), Line of March (LOM), the Communist Workers Party (CWP) and the Democratic Socialists of America endorsed Jackson’s candidacy. [3]

Communist Party support

The Communist Party USA's Daily World said on April 13, 1984 during the Presidential primaries:

- The answer to Reagan and Bush is to redouble efforts to build and strengthen the all peoples' front, a vital part of which is the campaign being waged on the issues by Jesse Jackson.

Communist Party USA vice presidential candidate Angela Davis added:

- The Jesse Jackson campaign is going to force the Democratic Party to speak on issues that they ordinarily would not address.

Gus Hall, when asked who the Communist Party USA would support for President in the 1988 election, said:

- As a political party we do not endorse candidates of other political parties. Communists as individuals work in the election campaign, even in the campaigns of other candidates, not only Communist candidates.

- I think our members will work for the candidates they think have the most progressive, most advanced positions. At this stage most members of the Party will be working for Jesse Jackson on the basis that he does have an advanced position. But we do not endorse any candidate, including Jackson.[4]

Houston CP

In 1988 the Houston Communist Party organized the local Rainbow Coalition.[5]

LRS, and the Jackson campaigns

Warren Mar, Organizing Upgrade, How Can the Left Participate in Electoral Campaigns? August 31, 2018:

- I worked on both the 1984 and 1988 Jesse Jackson for President Campaigns and was an open member of the LRS during my tenure. There was a big difference between the Jackson campaign in ’84 and ’88. In 1984 Jesse Jackson was less of a serious challenger and more of a messenger for progressives, including the African American community, that had seen the Democratic Party backpedal on all the gains of the civil rights movement won in the late 60’s and early 70’s. The new left organizations of the previous decade were mostly still in place during the 84 campaign, with a mass base in unions and communities of color.

- In 1984, many of the struggles Jesse Jackson was involved in that Bill Fletcher mentions in his “Lessons for today from the 1980’s Rainbow,” were the result of the left’s ability at that time to pull Jesse into struggles and in return give him reciprocal support for his electoral aspirations from places we had a base. For the LRS, this meant striking hotel workers, striking cannery workers, support committees for miners, and visits to Chicano barrios and Chinatowns. On college campuses he visited with Asian Students, Chicano Students in MECHA, and the Anti-Apartheid divestment and anti-sweatshop movements.

- Jesse Jackson deserves credit for his leadership in embracing racial justice and class inequality, but without the left’s participation, he would not have received the breadth of exposure or the depth of analysis, nor in return receive as broad a reception as he received outside of the Black civil rights movement where he had historic ties. The left, including the LRS, also challenged the lack of proportional delegates Jackson was entitled to at the 1984 Democratic Party Convention held in San Francisco. As luck would have it, the San Francisco Bay Area was the national center of many new left groups including the LRS. As a few of our elected Jackson delegates entered the Moscone Convention Center, thousands rallied outside, demanding an equal voice, based on the votes cast in the 1984 primary. That convention changed the electoral threshold required to gain primary delegates, laying the groundwork for Jesse Jackson to become a serious contender in 1988.

1988: The Demise of the New Left Organizations & LRS

- It would seem from the in-roads made in 1984 that the left would have had a bigger impact and made more significant gains in 1988, but while Jesse got more votes, the organized left and mass movements were much weaker after the 1988 elections. There were two trends we underestimated or ignored. First, this country was still moving to the right. Reagan easily trounced Mondale in the general election of 1984 and George Bush, likewise, dispatched of Dukakis in 1988. Worse, the Democratic Party was also moving to the right. I agree with Bill Fletcher on the left’s wishful thinking about the Democratic Party’s consolidation under the Democratic Leadership Council, which would usher in the Clintons and later accept Barack Obama. African American Democrats, elected into local office, would follow this trend. For those of us from San Francisco, Assemblyman, State Legislator, and San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown reflects this trend. By the 1980’s, Black mayors and Black municipal elected officials carried out the Democratic Leadership Council’s programs: attacking social safety nets, dismantling affirmative action and implementing the war on drugs, increasing the incarceration rates for Black and Brown people.

- But the other crucial trend, which many of us in our left bubble did not realize until too late, was that while the right was on the rise throughout the 80’s, our New Left movement was on the decline. There was a big difference in what remained of the New Left between 1984 and 1988. The LRS lasted longer than most, officially dissolving in 1990. By the 1988 elections and definitely by the debate on the Rainbow’s future in March 1989, most of the New Left groups were gone. I didn’t know it at the time but the LRS was also in critical condition.

- In 1984 I was a cook in a hotel in San Francisco, and an elected rank and file officer of Hotel and Restaurant Employees (HERE) Local 2. I pushed for Jesse Jackson’s endorsement in this capacity and as a delegate to the SF Labor Council. Most LRS members worked this way in some capacity or other. Most if not all of us were unpaid volunteers. By 1988 I was on as a full time paid organizer of the same Local. I got release time to go to work on the Jackson campaign as his Northern California Labor coordinator. I also went down to Houston to work on Super Tuesday. I worked as a full-time paid staff member of his campaign.

- In 1984, the LRS was not alone in my union local; there were many cadres from various left groups in hotels and some restaurants all over the city. By 1988-89 all those organizations and by extension, their cadres were gone. In 1988, there were more leftist staff in Local 2, including from LRS, but our cadres’ anchoring our base in various workplaces were mostly gone. This was the beginning of the end for the new left organizations, coinciding with the 1988 Jackson campaign, creating the perfect storm.

- Without a strong mass movement and base, the left is at a disadvantage in a united front electoral campaign Why is this important? I joined I Wor Kuen (IWK), a predecessor of LRS in 1974. We were growing exponentially and expanding across nationalities and geographical areas. As socialists we believed we should be based in the working class. We targeted industries to go into. I could speak Chinese and this added to my ability to organize the majority immigrant workforce. I went into HERE, because I was asked/told to. I held working class jobs as a Teamster, but working in union warehouses was still better than union restaurant work, which was immigrant based work and I was American born. I had done restaurant work in high school and hated it. I swore I would never do it again – until I became a leftist. Besides strategically placing cadre in union industries, IWK also had the line that we could run for elected union office but not take appointed union staff jobs. We explicitly opposed people who had never worked in an industry taking on union staff jobs.

- By the mid-80’s, we were having a harder time recruiting into the LRS. We changed the above policies slowly. First we started taking union staff jobs, but with cadre who had at least worked in the industry. This coincided with one area of recruitment that had not totally dried up: student work, especially in some of the campuses with an active anti-apartheid movement. Many new recruits in the 80’s came from some of the elite universities. Many factory and working class jobs in the 70’s were filled by student radicals who came off the campuses in the 60’s. The LRS student recruits leaving college in the 80’s would not consider going into factories or low level service work. They did however consider going directly into union staff jobs, work as legislative aides or on campaign work with politicians. They also moved directly into municipal government jobs, another position we opposed in the early days of IWK. We felt it was difficult to fight city hall when you work there.

- Some members in the national leadership of the LRS, in particular Asians from the IWK, also had ambitions to move on from revolutionary work and their educated backgrounds gave them rapid entre to Jesse Jackson's upper-echelon staff positions. The exceptions they made for the younger cadre of the 80’s on college campuses like Berkeley and Stanford fit in nicely with their own aspirations to move on. Many of the top national and regional staff positions in the ’88 Jackson campaign were occupied by not just members of LRS, but Asian Americans, formerly of IWK. This is one reason we sided with Jackson on the dissolution of the Rainbow into his personal campaign organization in 1989. His top staff members would stay with him, or with his blessing, go into local electoral campaigns of their own. This was not unique to LRS cadre. Many former members of CWP, CPML, LOM, etc. ran and won local offices after the 1988 campaign or got jobs as legislative aids or took positions as municipal bureaucrats.

Personnel

Go here for Rainbow Coalition personnel.

PUSH

Although money was a problem at first, initial backing came from Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton, Gary, Indiana Mayor Richard Hatcher, Aretha Franklin, Jim Brown, and Ossie Davis.[6]

National Rainbow Coalition

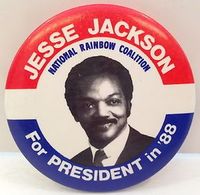

The National Rainbow Coalition (Rainbow Coalition for short) was a political organization that grew out of Jesse Jackson's 1984 presidential campaign. During the campaign, Jackson began speaking about a "Rainbow Coalition", an idea created by Fred Hampton, regarding the disadvantaged and welcomed voters from a broad spectrum of races and creeds. The goals of the campaign were to demand social programs, voting rights, and affirmative action for all groups that had been neglected by Reaganomics. Jackson's campaign blamed President Ronald Reagan's policies for reduction of government domestic spending, causing new unemployment and encouraging economic investment outside of the inner cities, while they discouraged the rebuilding of urban industry.

At the 1984 Democratic National Convention on July 18, 1984, in San Francisco, California, Jackson delivered an address entitled "The Rainbow Coalition".[7].

The speech called for Arab Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, youth, disabled veterans, small farmers, lesbians and gays to join with African Americans and Jewish Americans for political purpose. Whereas the purpose of PUSH had been to fight for economic and educational opportunities, the Rainbow Coalition was created to address political empowerment and public policy issues. After his unsuccessful bid for the Democratic nomination in 1984, Jackson attempted to build a broad base of support among groups that "were hurt by Reagan administration policies" - racial minorities, the poor, small farmers, working mothers, the unemployed, some labor union members, gays, and lesbians. [8]

Socialist support

Democratic Socialists of America did not endorse Jesse Jackson and the Rainbow Coalition in the 1984 election, but DSA did endorse Jackson and the Rainbow in 1988. Shakoor Aljuwani became the DSA staff person working to build support for the Rainbow. His work focused on building Labor for Jackson committees.

The following is from a 1988 statement by the DSA National Political Committee:

- “Supporting the Jackson candidacy is one important component of our efforts to help shift the political discourse in the Democratic party and the nation to the left. We work within the progressive wing of the Democratic party in alliance with others seeking to advance vital issues of justice, opportunity and economic democracy. DSANPAC will work with our allies to unite behind the most progressive Democratic party nominee to ensure the defeat of the Republicans in November.”[9]

Maoist influence

Louis Proyect first ran into Line of March when he was a member of Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) in the early 80s. They and the Communist Workers Party were the only left groups who worked in CISPES. The CWP, a Maoist sect, was best known for its disastrous confrontation with the KKK in Greensboro, North Carolina in 1979 that left five of their members dead. They had made the mistake of choosing to utilize armed self-defense as a tactic rather than building a mass movement against Klan terror.

In 1984 the CWP, LofM and the CISPES leadership decided to support the Jesse Jackson presidential campaign. For Marxists coming out of the CWP and LofM tradition, voting for Democrats is a tactical question. If there was ever any tactical motivation for voting for a Democrat, Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition might meet all qualifications. Many people, including Proyect, hoped that the Rainbow Coalition could develop into a third party but Jackson was too much of a careerist to make the kinds of tough choices Ralph Nader made. One year after the end of the Jackson campaign, the CWP dissolved itself with a number of its members finding a home in the Democratic Party, including Ron Ashford, a very capable African-American who represented the CWP in CISPES. Today Ashford is a HUD bureaucrat.[10]

Line of March

Line of March was heavily involved in both the 1984 and 1988 Jesse Jackson presidential campaigns.

1987 conference/Board

At the National Rainbow convention in Raleigh North Carolina, a new board was elected.

- Rick Adams

- Joseph Ahan

- Vicki Alexander

- Lavonia Allison

- Toney Anaya

- Billie Avery

- Rev. Willie Barrow

- Marion Barry

- Ken Blaylock

- Heather Booth

- Anne Braden

- Bruce Bushing

- Leslie Cagan

- Margaret Carter

- Rev. Benjamin Chavis

- Sherry Keason

- Wendell Chino

- Ed Coxen

- Barry Commoner

- Rep. Sherman Copeland

- Rev. Herbert Daughtry

- Ossie Davis

- Dave Dellinger

- Michael Diandria

- John David

- Rep. Al Edwards

- Daniel Ellsberg

- Arthur Eve

- Congressman Walter Fauntroy

- John George

- Maxine Green

- Rep. Luis Gutierrez

- Larry Hamm

- Merle Hansen

- Connie Hogarth

- Sasha Harry

- ...Yosefian

- Dolores Huerta

- Sonia Ivany

- Clark Johnson

- ...Kaliho

- Arthur Kinoy

- Maggie Kuhn

- Lawrence Landry

- Bert Lee

- Mae Louie

- Gwendolyn Lynch

- Robert Maestas

- Gene Mallet

- Julianne Malveaux

- Hilda Mason

- Rev. Sam McKinney

- Joe McMillan

- Bill Means

- Rev. Jack Mendelson

- Terry Cantano

- Mike Murase

- Henry Nicholas

- Hazel Oby

- Mario Obledo

- Camille Odeh

- Rosalinda Jalasias

- George Parris

- Gwen Patton

- Marion Penn

- Jan Pierce

- Rep David Richardson

- Wilson Riles

- Bruce Roseti

- Gene Royal

- Delores Sanchez

- Barbara Simmons

- Damu Smith

- Dr. Bill Strickland

- Percy Sutton

- Odette Turner

- Carlyle Terrell

- Benny Thayer

- James Turner

- Al Vann

- Sabina Virgo

- Maxine Waters

- Rep. Jesse Weinberry

- Linda Williams

- Polly Williams

- Butch Wing

- William Winpisinger

- Ricky Bradley

- Michele Hasketh

- President -Jesse Jackson

- VP/Finances - Emma Chapele

- VP/Policy - Leslie Baskerville

- VP/Arab Americans - James Zogby

- VP/African-Americans - C. Delores Tucker

- VP/Jewish Americans - Balfour Brickner

- VP/Latinos - Evelyn Linares

- VP/Asian-Americans - Cindy Ng

- VP/Native Americans - Rhonda Langford

Vote tallies

Overall, Jackson placed third in 1984, with 3.5 million votes, and the pundits who’d said he would be the party’s ruin watched as Walter Mondale, heedless of Rainbow constituents and their issues, crashed in defeat. In 1988, Jackson placed second, winning over 7 million votes, more than Mondale had scored in 1984; and 1,218.5 convention delegates, more than any runner-up in history. Again the pundits, warned of “certain and apocalyptic defeat” if Jackson were given a spot on the Democratic ticket. He wasn’t, and Michael Dukakis, as heedless as Mondale and hitched to Lloyd Bentsen, a DLC Democrat, suffered his own private apocalypse.

Rainbow Convention

At conferences in Houston and Washington DC, Jesse Jackson announce d the National Rainbow Coalition's Midterm Conference. He was flanked by Rep. Mickey Leland, chair Congressional Black Caucus, David Cortright of SANE, James Zogby of the Arab American institute, Clarence Mitchell, chair National Association of Black State Legislators, C. Delores Tucker, DNC Black Caucus, Arthur Kinoy Center for Constitutional Rights, and Marion Barry, chair, Conference of Black Mayors. [11]

Letdown

To speak with Rainbow warriors now is to confront a persistent, deep disappointment that in the spring of 1989 Jackson decided against institutionalizing the Rainbow as a mass-based, democratic, independent membership organization that could pursue the inside-outside strategy he’d articulated vis-à-vis the Democrats and build strength locally and nationally to leverage power for progressive aims. Instead, as Ron Daniels, who’d drawn up various plans for such an organization, puts it, Jackson opted for “a light and lean operation.” It was, he says, “a lost opportunity.”

Bill Fletcher, Jr. captures the general tenor of disappointment: “Jackson inspired a level of activity in electoral politics that I’ve never seen. He encouraged people who were cynical to get involved. The Rainbow pumped people up, and then it deflated them. And the problem is that it then becomes very difficult to reinflate. I think that he overestimated his own strength in the Democratic Party and was seduced by those, particularly in the black political establishment, that suddenly fawned all over him. But what he’d created, rather than a permanent Jackson wing of the party, was a very broad insurgency within and outside the party. And so, ironically, in demobilizing the Rainbow, he also committed a coup against himself.”

Privately, one of his close campaign associates said, “I think Jackson didn’t want to have to referee between different parts of his coalition. By 1988 the tensions were already clear. The activists were getting supplanted by the elected officials; the Congress people were telling the lefty radicals to tone it down. The sectarians in various places were trying to take it over internally, and you know the left has never solved that question. We had the most diverse, most little-d democratic, most American delegation anybody’s ever sent to a convention, in ’88.

But if we had just had grassroots little-d democratic votes everywhere, we’d have had a delegation made up almost entirely of black ministers, because they could outvote certainly the gay and lesbian representative, the white Central America activists. Some state coordinators are still catching hell for the choices they made.” No doubt, says Anne Braden, “he probably thought he had a tiger by the tail, and maybe he felt he couldn’t control it. But on the Rainbow board, people felt we were doing fine. He needed to trust the people more who really wanted to make it work.” Privately others say Jackson is incapable of engaging in the kind of dialogue and delegation of authority that sustaining that type of organization would have required.[12]

Lack of white "progressive" support

Between ’84 and ’88, as Cobble notes, “no one of any prominence among white progressives came to Jackson and said, ‘We want you to run’; none of the magazines, none of the organizations, only a couple of labor unions (AFGE, the Machinists, 1199). In ’88 the only large organization that wasn’t black that backed him was ACORN. The Nation didn’t endorse until April, which was pretty dang late. After ’88 Jackson clearly now is the frontrunner for the nomination. Did the unions say, ‘Jesse, let’s go, let’s start right now for ’92’? Did any of the liberal organizations? No. NOW announced it was putting together a commission to study a third party. Jackson’s the front-runner for the major-party nomination, and suddenly they’re thinking about organizing a third party!”

“Front-runner” talk always disconcerted leftists who cared more about the Rainbow’s movement potential. Yet whatever else he could or couldn’t do, Jackson was a proven, powerful candidate. His grassroots forays helped the Democrats win back the Senate in 1986 and propelled candidates into office at all levels. By the calculus through which liberal institutions ordinarily support Democrats, the nod to Jackson should have been uncontroversial. A labor official, asked why, after ’88, unions would not have seen where their own future best interests lay, said, “That’s not the way those people do business; they don’t do the outreach.” But there was nothing business-as-usual about Jackson, who’d walked picket lines for decades. Frank Watkins was more direct: “The reason labor didn’t do that is they’re racist. The reason civil rights organizations didn’t is they’re jealous. The reason the women didn’t is they’re suspicious.”

Someone else was doing outreach. In the spring of ’89, Al From, intellectual architect of the Democratic Leadership Council, paid a visit to Governor Bill Clinton in Little Rock. Unlike progressive forces, the backlash Democrats recognized the utility of a charismatic candidate, and of starting early. For 1984 they’d won rules changes, introducing the concept of “superdelegates” to shift power from party activists to elected officials. Jackson managed to negotiate limits on those delegates in 1984. The next year the DLC formally constituted itself. For ’88 it advocated one big Southern primary, Super Tuesday, to secure the nomination, it expected, for a white conservative. Jackson swept Super Tuesday, besting the DLC’s favorite son, Al Gore. When Jackson then took 54 percent of the vote in Michigan, what appeared in tantalizing prospect was a new party paradigm–neither the New Deal alliance of Northern liberals, blue collars and Jim Crow, nor post-McGovern liberalism with its smorgasbord of interests and its white elite firmly in charge of portion-control. Party liberals had a choice; they chose reaction.

“The error,” says Kevin Gray, who coordinated Jackson’s winning campaign in South Carolina in ’88 and organized for the ’84 win as well, “was in assuming we ever left the Age of Reagan, and not carrying the critique to the Age of Clinton. Where Jesse dropped the ball is he became a Democrat. Instead of a small-d democrat, he became a big-D Democrat–except with an asterisk.”[13]

1990 conference

In May 3-6, 1990 the NRC held a successful conference in Atlanta, attended by over 1,000.

Bernie Demczuk, national labor coordinator of the Rainbow, organized a contingent. Jack Sheinkman, president of the ACTWU, hosted a labor breakfast.

California Assemblywoman Maxine Waters, has been the strongest leader in the California Rainbow, also attended, as did Leslie Cagan, a Rainbow board member.[14]

Cuba visit

In December 1993 Rev. Jesse Jackson and Local 1199 president Dennis Rivera spent a 5 day holiday in Havana Cuba. the two Rainbow Coalition leaders pledged their support for HR 2229, introduced into Congress by Rep. Charles Rangel, to end the blockade and normalize relations.

Jackson was invited by the Cuban Ecumenical Council. The pair met with Cuban leader Fidel Castro, Foreign Minister Roberto Robaina and Finance Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez.[15]

Passing the torch

According to Paul Ortiz;

- Likewise, there were many Obama activists who had campaigned for the Rev. Jesse Jackson in 1984 and 1988. It is impossible to imagine Senator Obama's victory without the precedent of Jackson's Rainbow Coalition. The Rainbow excited and recruited tens of thousands of gay, Latino, Native American, white, Asian, and African-Americans into electoral politics, social movements and union organizing in the US in the 1980s. The Rainbow sustained and supported numerous progressive politicians, including Paul Wellstone, Tammy Baldwin and Harold Washington. The Rainbow Coalition - and Jackson as leader - had many limitations. Even so, the organization provided one of the few spaces for progressive movement organizing to take place in the Age of Reagan. The Rainbow increased working-class voter registration, promoted Shirley Chisholm for vice president, stood in solidarity with the Pittston coal strike, and was a counterweight to the conservative Democratic Leadership Council.[16]

According to JoAnn Wypijewski, writing in The Nation July 15, 2004;

- Electorally, this year’s Illinois Senate race is another stage in the process. Barack Obama, 42, is likely to become the only black senator come November. At the Rainbow/PUSH convention in June, the mere mention of his name by John Kerry prompted a standing ovation. As Manning Marable noted, Obama (like Tammy Baldwin and Jesse Jackson, Jr.) is representative of “that generation of the left that came to political maturity in the 1980s informed by three pivotal motions, around AIDS, antiapartheid and the Jackson campaigns.” Coming up his own way–Harvard, local elective office, “the Rainbow via Tiger Woods,” as journalist John Nichols aptly put it–Obama nevertheless followed a Jacksonian strategy, solidifying his black base, then appealing to Latinos, Asian-Americans, white liberals, farmers, gays and lesbians, labor, with a message of economic justice and opposition to the war that, again, presents an alternative to DLC politics. For a party in search of stars, Obama could be it. But as his friend Camille Odeh, a 1988 Jackson delegate, longtime Palestinian organizer and executive director of the South West Youth Collaborative in Chicago, cautions: “I wouldn’t put so much on the individual. We need more than that on the left–a discourse around ideologies and, beyond only activism, genuine grassroots community organizing. Then when the individual can’t pull through or has to compromise, people don’t get demoralized.”

- Perhaps it will take the generation behind Obama for that. At a recent conference of Democratic progressives, the younger cohort, more reflective of rainbowism than their elders, were talking about technology but also “beauty parlor/barbershop” organizing; about voter registration but also about using electoral politics tactically, because “our issues don’t go away after the election”; about remembering that “the people need hope” but also regarding the Democratic Party without illusion. The name Kerry never came up. Their issues fell within what Jackson had called “the trilogy of racism, exploitative capitalism and militarism,” what Martin Luther King had first named “the triple evils.” In their 20s mostly, they weren’t quite advocating a “restructuring of the whole of American society,” as King had, but they did speak of imagining a different world. In their discussion there was the resonance of something.

- Jack O'Dell, an old soldier of the left, who’d worked with Dr. King, worked with Jackson shaping the international agenda said “There are moments,” he’d said, “and we have to take from those moments all that is positive, because that’s our inheritance. Because of Jesse Jackson’s campaigns, we know how to build a grassroots campaign. Without them, we might have the analysis but not the experience. We must still ask ourselves how we can reinvigorate electoral democracy. We can’t drop out, as if what we don’t like about electoral politics will go away because we abstain. Movements are directed toward political power, and wherever we can get a piece of it, we have to try to get it and hold on to it. Now, we know what Bush is. If we are victorious in defeating Bush, then our assignment is to make what we can of Kerry. And our job begins the next day.”[17]

Reboot the Rainbow: Unusual Alliances, the 99% and Fighting to Win

Wednesday March 14 2012 Counterpulse 1310 Mission Street San Francisco Panel discussion "Reboot the Rainbow: Unusual Alliances, the 99% and Fighting to Win".

In the 1960s the Black Panther Party for Self Defense joined with the Puerto Rican Young Lords and the poor White Young Patriots Organization in the Original Rainbow Coalition (pre-Jesse Jackson). The model of "organize your own but fight together" was an attempt to build broad unity in dispossessed communities while dealing with the realities of racialized capitalism head-on. Come join a discussion of this history and what its going to take to keep the 99% together for the long-haul.

Panel discussion will include a slideshow of the art of the Rainbow Coalitions. On the panel: Pam Tau Lee (member of I Wor Kuen), Joe Navarro (Los Siete De La Raza Defense Committee), Killu Nyasha (Black Panther Party) and Amy Sonnie and James Tracy (co-authors of Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels and Black Power: Community Organizing in Radical Times).[18]

Right to the City/new Rainbow Coalition

According to Mel King there’s an additional factor that figured significantly in Martin Walsh’s successful mayoralty campaign in 2013.

A group called Right to the City, composed of various organizations working on access to affordable housing, good jobs, quality education, and sustainable community development, seeks to enable a cross section of racial, ethnic, and income groups to remain and participate in all aspects of Boston.

The group’s members, a new rainbow coalition, are in the forefront of such issues as foreclosure blockades to protect people’s homes, stopping no-fault tenant evictions, and fighting alongside unions for construction jobs.

Following its questionnaire to both mayoral candidates, the group felt Walsh was more responsive to its concerns. Having encouraged these young adults to do this analysis, Mel King joined with them. At our endorsement announcement, I admired their commitment to looking forward and not wallowing in the past.

They saw a candidate who willingly shared parts of his life that indicated he has the capacity for change. He invited them to work with him to make a difference for all the city’s residents.

- Both at the endorsement event, when a high school student spoke, and at Fields Corner, where a diverse group rallied, I saw evidence of ways Walsh’s campaign included people. A personal highlight was watching the candidate join in singing a song I wrote: “We are in harmony; once to every generation comes the chance to change the world.”[19]

Infuence on Obama's election

Steve Phillips August 10, 2013

Honored to be on panel at Chinese Historical Society commemoration of March on Washington — with Francis Wong and Jon Jang at 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington.

Jon Jang Steve, you and I were one of the few I know that share how the Jesse Jackson Rainbow Coalition had an impact on the election of President Obama.

Moderator Doug Chan, and the CHSA staff Gerard Veronica Sese, Chris Heins, Nolan Chow, Johnson Zheng, Amy Lam.[20]

External links

References

- ↑ Affiliates

- ↑ [http://www.leftvoice.org/The-DSA-in-the-Democratic-Party-Labyrinth Left Voice, The DSA in the Democratic Party Labyrinth The DSA in the Democratic Party Labyrinth Tre Kwon JimenaVergaraO June 19, 2017]

- ↑ Left Voice, The DSA in the Democratic Party Labyrinth The DSA in the Democratic Party Labyrinth Tre Kwon Jimena Vergara June 19, 2017

- ↑ name=page43

- ↑ The art and science of building the Communist Party, BY:BERNARD SAMPSON| JULY 5, 2018

- ↑ [Jackson PUSHes On". Time. Time Inc. January 3, 1972. Retrieved May 1, 2002]

- ↑ ["Top 100 Speeches" American Rhetoric. 2007. Retrieved September 5, 2007]

- ↑ [Shapiro, Walter (April 11, 1988). "Taking Jesse Seriously (page 9)". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved May 1, 2008]

- ↑ Democratic Left, Whither the Rainbow? A Golden Opportunity, 1986: DSA Debates Its Role in Electoral ChallengesPosted by Dsa 🌹 on 06.19.17

- ↑ Louis Proyect: The Unrepentant Marxist August 3, 2013A critique of Bob Wing’s “Rightwing Neo-Secession or a Third Reconstruction?”

- ↑ [The Rainbow Organizer Vol 3, no 1]

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Our Struggle/Nuestra Lucha. Vol. 8, No 2-3, summer 1990

- ↑ PW R'bow coalition leaders call for end to blockade, Jan. 8, 1994, page 15

- ↑ On the Shoulders of Giants Tuesday, 25 November 2008 16:16 By Paul Ortiz, t r u t h o u t

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ San Francisco | Arts + Action | Racial Justice 3/14/2012 Title: Reboot the Rainbow: Unusual Alliances, the 99% and Fighting to Win

- ↑ Boston Globe, A new rainbow coalition backs Martin Walsh, Mel King, NOVEMBER 17, 2013

- ↑ [4]