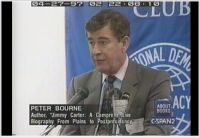

Peter Bourne

Peter G. Bourne is a professor, psychiatrist, activist, former government official, and author.

Background

He was born in Oxford, England and educated at the Dragon School. Bourne received an MD from Emory University and an MA in anthropology from Stanford. Bourne served as a captain in the US Army, specifically with the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.[1]

Bill Richardson Connection

From Peter Bourne's personal website:[2]

- "When I was in the White House President Carter had charged me with finding ways to begin a dialogue with the various countries with which the US did not have diplomatic relations. In most instances, Cuba, Angola, Iraq, and South Africa, this amounted to medical diplomacy initiating various forms of medical collaboration. With Outer Mongolia we began a dialogue about wild life management. With North Korea I was unable to get them to collaborate on anything. This experience prepared me well for a number of initiatives undertaken with Congressman Bill Richardson in the mid-nineties during the Clinton administration.

MEDICC

Excerpt from Peter Bourne's personal website:[3]

- Peter Bourne is Visiting Senior Research Fellow at Green Templeton College, University of Oxford, Vice Chancellor Emeritus of St. George's University in Grenada, West Indies, and Chairman of the Board of Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC).

[...]

- "In the mid-1990s while serving as the chairman of the board of the American Association for World Health Dr Bourne was asked to coordinate the implementation and publication of a foundation-funded study of the impact of the US embargo on health and nutrition in Cuba. The report received widespread note in the US and Europe. It also drew attention to the excellence of the Cuban health system, especially in providing primary care. With additional foundation funding Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba (MEDICC) was formed to enable US medical students, residents and other health professionals to do electives in Cuba. Dr Bourne became the chairman of the organization’s board. Over the next six years more than 1,500 US students spend six week stints working with Cuban family physicians.

- MEDICC also became increasingly a “health bridge” between the medical communities in the US and Cuba. Because of changes in US government regulations in 1974 it was no longer possible to send medical students to Cuba. MEDICC then expanded its activities in other areas especially taking research groups to Cuba and expanding its publication of MEDICC Review, the only English language publication dealing with Cuban health care and medicine. With two other MEDICC board members Dr Bourne co-produced the feature length documentary !Salud! showing the Cuban health system and the role of Cuban doctors around the world.

Honoring Fidel Castro

On November 26, 2016, Peter G. Bourne, Chair, MEDICC Board of Directors, Nassim Assefi, MEDICC Executive Director, Gail Reed, MEDICC Founding Director honored Cuban communist dictator Fidel Castro.

Verbatim from the Medical Education Cooperation with Cuba website in a tribute titled "MEDICC Remembers Fidel Castro as Leader of Health for All":[4]

- November 26, 2016 – Fidel Castro is gone, but his name still arouses passions over 60 years after his first appearance on the world political stage as a young rebel leader. In the debate swirling around his legacy, of two things there can be no doubt: while he was Cuban, he was also bigger than Cuba, the last of the larger-than-life giants of 20th century leadership.

- And just as important, he was the driving force and main architect of universal health care in Cuba, a public health system responsible for making Cubans some of the healthiest people in the world. Built upon the notion of the right to health, he first outlined this vision in the program of the movement he led to victory on January 1, 1959.

- As a result of his leadership, the new government dedicated itself first to health and education for all. In 1960-61, newly graduated doctors, backpacks in hand, headed for the countryside and mountains to take health care to people there for the first time, which coincided with a massive Literacy Campaign that taught some 700,000 Cubans to read and write.

- Over the years, President Castro took an abiding interest in health and was at the forefront of promoting advances in health care, research and medical education: establishing rural hospitals and a national network of hundreds of community-based clinics, making prevention a cornerstone of training and service; generating extraordinary investments in biotechnology to develop novel vaccines and cancer therapies, and specialized services for Cuban newborns with heart disease. Finally, he considered the most significant “revolution within the revolution” to be the creation in the 1980s of the family doctor-and-nurse program, posting their offices on every block and farmland in Cuba.

- The outcomes of these efforts were not achieved by one man, but by 500,000 Cuban health workers, who were able to count on health as a government priority. Together, they faced dengue and neuropathy epidemics; and the scarcity of medicines, including for HIV-AIDS patients, after the collapse of the socialist bloc and tightening of the US embargo on Cuba in the 1990s. Their dedication has won a healthier nation.

- Under Fidel Castro’s leadership, Cuban health professionals also began volunteering to serve abroad as early as 1960, responders to earthquake-devastated Chile; and in 1963, the first long-term service was offered by doctors sent to newly independent Algeria.

- Despite invasions and attempts on his own life, Fidel Castro continually demonstrated an attitude of openness towards the US people. He offered thousands of specially trained Cuban doctors to help New Orleans recover after Hurricane Katrina, a medical team named after Brooklyn-born Henry Reeve, a hero of Cuba’s independence war against Spain. He opened the scholarship doors of the Latin American School of Medicine to young, low-income US students, after a request from the Congressional Black Caucus. In his words, the school’s goal: “The doctors trained here should be the kind needed [by people] in the countryside, villages, marginalized neighborhoods and cities in the Third World. And also in immensely wealthy countries, such as the United States, where millions of African-Americans, Native Americans, Latino immigrants, Haitians and others, lack health care.” Since its opening in 1999, the Latin American School of Medicine has enrolled over 200 US students and graduated some 30,000 physicians from 100+ countries.

- A MEDICC group of public health and medical educators was the last US delegation to meet with President Fidel Castro before his illness in July, 2006. As was customary, the gathering lasted for the whole night. But at the heart of our conversations was not global politics… but rather health, cochlear implants for blind-deaf Cuban children, a call to the Cuban medical team in East Timor, even the potential for US-Cuba cooperation in health and medicine. For 12 hours, health was at the top of our mutual agenda.

- We can only hope that, going forward, the US-Cuba cooperation in health envisioned during that long night– and later ratified by Presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro– can endure and expand, to benefit people in both our countries.

- To the Cuban people, to Fidel Castro’s family, we extend our heartfelt condolences and appreciation for his life-long dedication to health worldwide.

- Peter G. Bourne, Chair, MEDICC Board of Directors

- Nassim Assefi, MEDICC Executive Director

- Gail Reed, MEDICC Founding Director

Jimmy Carter friendship

Bourne initially became involved in Democratic politics in the early 1970s. He and Jimmy Carter are described as "very old friends." In 1972, Bourne held the number two position in the White House's SPecial Action Office on Drug Abuse.[5] In an interview, Carter said: "[Bourne] was the first person to suggest I run for President, fall of 1972. It was from that memorandum that our campaign was based"[6]

White House scandal

On July 19, 1978, Bourne was placed on leave after it was discovered that he had used a false name to prescribe Quaalude -- a sedativie-hypnotic -- to a White House aide.[7] Although initially placed on leave, Bourne resigned after it was reported by a Washington Post columnist that Bourne had smoked marijuana and sniffed cocaine at a party. Bourne denied using cocaine.[8]

Institute for Southern Studies

Bourne was a member of the Institute for Southern Studies from 1969-1986.[9]

In 1970, Bourne helped found the Institute for Southern Studies, along with Sue Thrasher, Julian Bond, John Lewis, N. Jerold Cohen and Howard Romaine. When the organization was founded, the initial work was done preforming research, holding seminars, and performing activism against the Vietnam War.[10]

Founding Board members

| Institute for Southern Studies Incorporating Documents in North Carolina |

|---|

|

|

The Institute for Southern Studies was incorporated in the state of North Carolina on July 28, 1989. The founding members listed on the incorporation papers:

- Julian Bond President, from Atlanta, Georgia

- Peter Bourne, from Washington, D.C.

- N. Jerold Cohen, from Atlanta, Georgia

- John Lewis, from Atlanta, Georgia

- Marcus Raskin, from Washington, D.C.

- Howard Romaine, from New Iberia, Louisiana

- Robert Sherrill, from Washington, D.C.

- Sue Thrasher Secretary, from Atlanta, Georgia

- Elizabeth Tornquist, from Durham, North Carolina

Legalizing heroin

In the 1970s, Bourne was quoted as being in favor of legalizing heroin. "Legalizing heroin may increase the number of addicts, but it would reduce the cost of addiction," he said in an interview.[11]

Fidel Castro

Bourne authored a biography in 1986 of Fidel Castro titled, Fidel. Bourne was granted access to Cuban archives and granted interviews with individuals close to Castro.[12]

Personal

Bourne is married to Dr. Mary Elizabeth King. They reside in Oxford, UK and Washington DC. Mary is a described "peace and nonviolent action" activist.[6]

External links

References

- ↑ Peter Bourne Official Website "Biography," Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ Travels with Bill (accessed January 31, 2024)

- ↑ Bio (accessed January 31, 2024)

- ↑ MEDICC Remembers Fidel Castro as Leader of Health for All (accessed January 31, 2024)

- ↑ Green Templeton College Magazine "Autumn 2009," Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 Peter Bourne Official Website "Home Page" Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ New York Times "Carter's Aide, Linked to Issuing False Prescription, Takes Leave; Not Available for Questioning Carter Adviser, Linked to Issuing a False Prescription, Takes Leave Salary Is Unaffected," July 20, 1978

- ↑ Florence Times "Bourne incident raises suspicision over use of drugs," July 23, 1978

- ↑ Peter Bourne Official Website "Resume" Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ NYU Southern Student Organizing Committee "Where are they now?" Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ Executive Intelligence Review "Volume 3, Number 43, October 25, 1976" Accessed January 8, 2012

- ↑ Amazon.com "Fidel: A Biography of Fidel Castro" Accessed January 8, 2012