Difference between revisions of "Richard Durham"

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

==Black Press Institute== | ==Black Press Institute== | ||

| − | In 1987 Richard Durham (in memoriam) was on the Board of Directors of the [[Black Press Institute]]. Durham was a founding board member<ref>Black Press Institute Letterhead October 5 1987</ref>. | + | In 1987 [[Richard Durham]] (in memoriam) was on the Board of Directors of the [[Black Press Institute]]. Durham was a founding board member<ref>Black Press Institute Letterhead October 5 1987</ref>. |

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 16:00, 3 February 2017

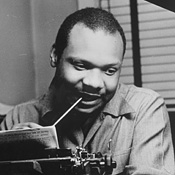

Template:TOCnestleft Richard Durham (1917-1984) was a Chicago writer, broadcaster and activist.

He was married to Clarice Durham and was the older brother of Earl Durham.

Early life

Richard Durham was born on September 6, 1917 in Raymond, Mississippi, a small rural community in Hindes County. His father, a farmer, moved the family to Chicago when Durham was seven years old. Durham attended Hyde Park High School and Northwestern University[1].

Radicalization

While at Northwestern, Durham joined the Communist Party USA infiltrated Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration and received training and experience as a radio scriptwriter. When this project ended, Durham joined the staff of the Chicago Defender[2].

Marriage

Richard Durham met Clarice Davis in the early 1940s while working with the National Negro Congress. The couple married in 1942. During their married life, Mrs. Durham made significant contributions to Durham's work by reading, editing and typing many of the Destination Freedom scripts[3].

Early career

Durham's first major experience with radio came between 1946 and 1948 when he wrote scripts for a series on black achievement, Democracy U.S.A., which aired on WBBM, a CBS station.

While he was recovering from an injury, his sister gave him a typewriter and he began to write poetry and soon won first prize in a poetry contest. Durham also wrote scripts for Here Comes Tomorrow, a black soap opera that aired on WJJD. Destination Freedom, a dramatic radio series on WMAQ in Chicago, brought the freedom struggles of African Americans to Chicago listening audiences on Sunday mornings between 1948 and 1950[4].

The premier of Destination Freedom on June 27, 1948 signaled a landmark in African American broadcasting history.

Durham worked talented young intellectuals and entertainers including Oscar Brown Jr., Studs Terkel, Janice Kingslow, Wezlyn Tilden, Fred Pinkard and Vernon Jarrett.

- Durham developed scripts that captured the lives and struggles of everyday men and women as well as prominent African Americans. Unlike the typical radio fare of its time, Destination Freedom featured social dramas that eloquently appealed for racial justice. As Durham explained, "the real-life story of a single Negro in Alabama walking into a voting booth across a Ku Klux Klan line has more drama and world implications than all the stereotypes Hollywood or radio can turn out in a thousand years."

Durham cast black actors in leading roles and told the stories of activists and leaders including Frederick Douglass, Toussaint L'Ouverture and Mary Church Terrell, writers and artists including Richard Wright, Katherine Dunham and Gwendolyn Brooks[5].

Richard Durham researched his shows in the Chicago Public Library with Vivian Harsh's assistance.

- ...close readings of autobiographies, monographs and speeches and skilled scriptwriting brought these historical and contemporary figures to life in poignant detail on Destination Freedom. Certain of the redemptive power of black history and education, Durham went beyond recounting the biographies of these figures and focused on the ways that they overcame racial injustice through resistance. Durham challenged network protocols to ensure that the series featured black women as equally important, history-making figures.

The series lacked a sponsor for most of the time it aired on WMAQ, but by relying on his earlier connections, Durham persuaded the Chicago Defender to fund the first weeks of the broadcast and the Urban League sponsored several broadcasts in 1950. Despite Durham's efforts to exercise authorial control over the series, WMAQ edited, controlled final script approval and rejected the more controversial stories of the lives of Nat Turner and Paul Robeson. Despite these conflicts, the station recognized the import and the success of the show when in 1949, it won a prestigious first-place award from the Institute for Education by Radio. On the anniversary of its first episode, Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson commended the program for its efforts in increasing racial tolerance and in educating the public on the contributions of African Americans[6].

- Despite these accolades, WMAQ canceled Destination Freedom in 1950, just as the rising tide of anti-Communist conservatism began to adversely affect radio and the arts.

Union writer

In the 1950s, Durham worked as the national program director of the communist controlled United Packinghouse Workers of America. Durham was hired to write a pamphlet on the accomplishments of the union's anti-discrimination department. The pamphlet, "Action Against Jim Crow: UPWA's Fight for Equal Rights," described the progressive work of the union to end job discrimination and to elevate women to equal status and equal pay in the workplace.

The union was so pleased with Durham's work that they hired him as the head of the program office and he wrote and developed materials to publicize the union's programs and events. But conflict arose as Durham continued to put pressure on the union to support and to prioritize black advancement. In 1957, he was forced to resign[7].

Du Bois Theater Guild

In the 1950's Chicago's Du Bois Theater Guild was one of the first groups to stress "Black Awareness" in its theater philosophy.

Founding members included Richard Durham, Vernon Jarrett, Oscar Brown, Jr. and Janice Kingslow.[8].

Nation of islam

After leaving the Packinghose Union, Durham worked as a freelance journalist. In the 1960s, he became the editor of Muhammad Speaks, the weekly publication of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam. Durham sought to provide an international perspective to the newspaper and included several articles on the independence struggles of African nations in the 1960s[9].

While Richard Durham was editor Elijah Muhammad purchased the four-story Muhammad Speaks Newspaper Plant and Cold Storage building. The facility housed a meat processing plant as well as a four-color Goss “Suburbanite” printing press, capable of turning out 50,000 copies per hour. In 1969 a fledgling Black printing crew helped the newspaper make the transition into printing industry, as well as journalistic, leadership, going on line and producing the 400,000 per week press run, entirely in-house.

Durham, who presided over a great expansion in the newspaper’s circulation and international respect during the 1960s, was succeeded by John Woodford, another former Ebony editor and writer in 1970. Woodford also became close to the Communist Party USA. John Woodford expanded the newspaper’s coverage beyond simply a hard news journal with arguably the best coverage of Africa and the non-aligned movement in any U.S. newspaper, with features on the arts and music which were richly illustrated with photographs by Chester Sheard, Hassan Sharrieff and Robert Sengstacke[10].

Writing and broadcasting

In 1971, Durham created a television series, Bird of the Iron Feather, which aired on WTTW, a local PBS station in Chicago. Described as a "soul drama" and funded by the Ford Foundation, this series was praised for introducing more authentic television programming and for portraying African American life in a more realistic fashion. Given the dearth of blacks in television production, Bird of the Iron Feather broke new ground by being almost exclusively written, directed and produced by blacks. While working as an editor for Muhammad Speaks, Durham was asked to assist Muhammad Ali in writing his autobiography, The Greatest, which was published in 1977[11].

Afro-American Patrolman's League

After being on the police force for about a year, Officer Buzz Palmer experienced the “shoot to kill” order issued by mayor Richard J. Daley during the Black uprisings and looting that occurred on the Westside of Chicago following the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Those events had a significant impact upon him.

Several Black police officers became concerned for the safety of unarmed Black leaders and Black citizens in general, being killed by white reactionaries. Officer Palmer decided to organize Black officers and began with a small cadre who also had not been on the force very long. Renault “Reggie” Robinson, Curtis Cowsen, Willie Ware, Wilbur Crooks, Jack Dubonnet and Tom Mitchell, who was not a police officer and Palmer, became the Afro-American Patrolman’s League. Howard Saffold and others came shortly, thereafter. They met initially in Palmer’s apartment and later, after chipping in, opened their first office on east 63rd Street.

Understanding that in order to adequately defend and protect the Black community, this small band of Black officers would need an umbrella of support. The endorsement of Black organizations in Chicago was imperative.

Richard Durham, although not a Muslim, editor of Muhammad Speaks was recruited. He convinced Palmer that Black police needed to demonstrate their support of the community and thus the slogan “We Support the Black Community” was born. [12]

Working for Harold Washington

Richard Durham wrote numerous speeches for Chicago's first African American mayor, Harold Washington, in the 1980s[13].

Death and memorial

Richard Durham died on April 27, 1984 while on a trip from Chicago to New York. At the time of his death, Durham was researching the life of Hannibal, the illustrious Carthagenian warrior who planned to conquer Rome. Mayor Harold Washington delivered the eulogy at his memorial service and a number of famous Chicagoans including historian Dempsey Travis, entertainer and former Destination Freedom cast member Oscar Brown Jr. and Congressmen Charles Hayes and Gus Savage attended the service.

In August 2007, Richard Durham was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame[14].

Black Press Institute

In 1987 Richard Durham (in memoriam) was on the Board of Directors of the Black Press Institute. Durham was a founding board member[15].

References

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ Black World/Negro Digest Apr 1973 p 28

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://www.finalcall.com/national/savioursday2k/m_speaks.htm

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ Founding of the Afro-American Patrolman’s League, written by Edward “Buzz” Palmer titled “A Voyage of Discovery” and can be read in its entirety in a publication being written by Dr. Useni Perkins scheduled to be published in 2008 by Third World Press.

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ http://mts.lib.uchicago.edu/collections/findingaids/durham.html

- ↑ Black Press Institute Letterhead October 5 1987